The primary goal of the programme developed by the Subcommittee on Lunar Exploration is to perform manned spaceflight to the Moon and its environs. A secondary goal is the development of technology and infrastructure to support long-term operations in lunar space and on the lunar surface.

The SLE was first convened in 1960, after two years of Leibnitz/Napier spaceplane operations, and made its initial report in June of that year. This contained the following summary:

There are two broad options for the overarching objective of the program over the next few years: developing space stations in Earth orbit, or sending crewed missions into lunar space. The latter poses some difficulties, as a spaceplane like the Napier would not survive atmospheric re-entry from a translunar trajectory, while propulsively braking its mass to LEO speeds would require sending a very heavy vehicle to TLI. The Subcommittee on Lunar Exploration identified two feasible approaches: a manned capsule with ablative heat shielding (similar to the smaller capsules used to recover photographic film), or a lightweight translunar "taxi" which propulsively brakes back into LEO to rendezvous with a spaceplane. Manned capsules are an untried concept and most members of the Committee are reluctant to endorse ballistic re-entry of crew, although a research program toward a one-man capsule is already under way which may resolve some of the unanswered questions. The "translunar taxi" would almost certainly require an Earth-orbiting space station as a staging point for the necessary multiple-rendezvous architecture (with, probably, a separately-launched TLI stage to dock with the taxi, as well as the launch of the crew aboard a spaceplane). Advanced missions (such as attaining low lunar orbit, making long-term stays there, and perhaps even a manned lunar landing) would certainly require a propellant storage depot in lunar orbit. Consequently, the Committee's view is that the development of docking systems and space stations should be the first phase in any next-generation program. The decision on whether to use these capabilities for lunar exploration, or to focus on establishing a long-term scientific outpost in LEO, can safely be left for future consideration at a time when the practice and limitations of docking and modular orbital assembly are more fully understood.

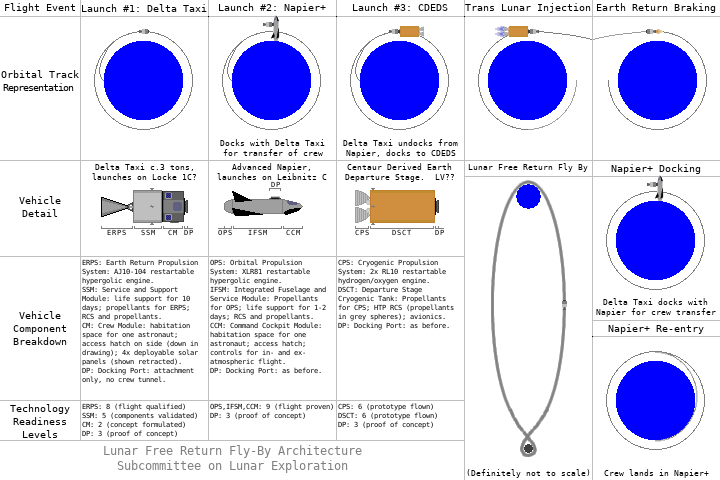

In an appendix, the SLE's outline designs for minimal "translunar taxi" systems were described.

The one-man cabin together with life support supplies and docking hardware is assumed to weigh not more than 800kg. A single propulsion stage with a pair of AgenaD engines suffices to boost onto a lunar free-return trajectory and subsequently brake back into low Earth orbit. This could be launched part-fuelled on a Grotius-derived LV and topped up with tanker flights; alternatively a larger upper stage (perhaps clustering RL10s or using a larger hydrolox engine) could launch the stage fully fuelled. Alternatively a Delta stage could perform the braking (with an extra 500m/s or so for manœuvres) and a Centaur could serve as the TLI stage; a fully-fuelled Centaur EDS may be within the throw capability of a six-booster Grotius variant; but this would require the dockings to be performed rapidly to minimise boiloff of the Centaur's propellants. Another possibility is an all-up launch using a twin-RL10 stage for TLI, though the crew would still need to launch separately as the "taxi" would not survive an aborted launch (so boiloff would still pose difficulties). All these variants show that a mere one-man lunar fly-by is right on the limit of attainability with currently practical launch vehicles.

The initial plan proposed by the SLE.

The "Grotius" LV mentioned here was similar to the Leibnitz series but with more than two (H-1) LFBs. It was not very cost-efficient as its performance was held back by the low thrust of the Tartaglia sustainer with its LR105 engine.

In accordance with the Committee's recommendation, lunar plans were shelved for the time being and the Lagrange Space Station, a primitive modular station with habitable space for up to 4 occupants, was launched the following year into a 400km/28.6° Earth orbit.

Over the course of 1962 a series of gradually more ambitious Station operations were performed, culminating in the crew rotation in October where NTF-3 and -4 overlapped; for the period of the handover, both Napier spaceplanes and four astronauts (Timur Vasilyevykh, Nikolay Tikhonov, Eric Welch and Catherine Graves) were at the Station; the latter pair then remained on-station for two months, setting an endurance record as well as (with the three weeks of NTF-3) a record for continuous human presence in space.

Another programme which ran during this time involved placing propellant depots in low lunar orbit (these missions were named Barrow) holding storable hypergolic propellants, and using them to support Lunar Sample Return missions; the first of these was Laplace 6, which with the help of four Barrows brought its collection of moon rocks to LEO, where a Napier flight (NEF-6 flown by Brian Newman) picked them up and landed them on Earth.

Later, the Barrow II, a larger depot launched by an Euler A, was developed, reducing the per-kg cost of delivery. This Euler launch vehicle family was also a key component; the large hydrolox J-2 engine of its upper stage enabled significantly heavier payloads than Leibnitz or Grotius vehicles without much increase in cost. Besides propellant deliveries, it is also the launch vehicle for the Earth Departure Stage used to send the Delta Taxi to the Moon, and has found other uses in e.g. sending unmanned probes to the gas giants.

During 1963 the lightweight crew cabin for the Delta Taxi was developed, and we began training astronauts to operate it.

The first mission performed under the auspices of this new manned programme was TPF-1, a shakedown of the Delta Taxi in Earth orbit, which took place in November 1963. NTF-5 (Napier 1), flown by Peter Chapman, met the Taxi Quester at Lagrange Space Station, where Rebecca Reid transferred from the Napier's passenger seat into the Taxi. A prograde burn with a little less than half the Taxi's ΔV lofted it into an elliptical orbit with an apogee over 8,000km, chosen to have double the period of the Station's own orbit. At the next perigee the Taxi braked back into LEO, Rebecca docked to the Station, and went home aboard Napier.

See an unsorted folder of images from this mission.

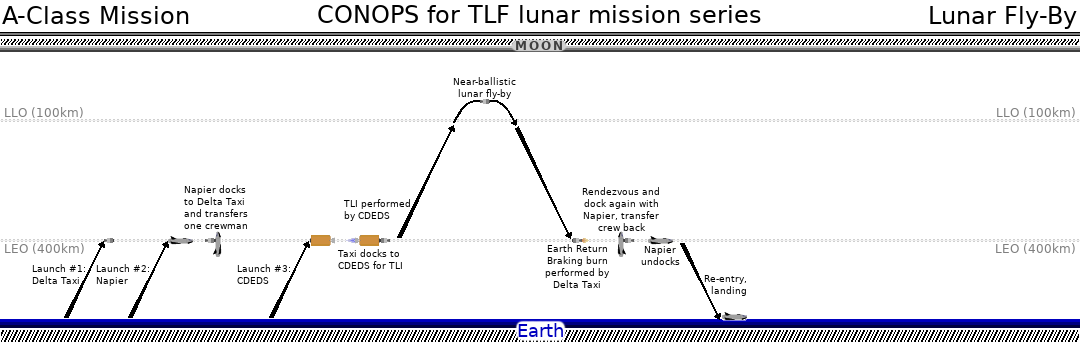

With all the pieces in place, manned missions to the Moon began early in 1964. Two mission classes were designated, the A-class fly-by and the B-class orbital mission.

The CONOPS diagram for the A-class lunar-flyby mission. (Note that these CONOPS diagrams do not show the Lagrange Space Station, which is used as a meeting-point in LEO.)

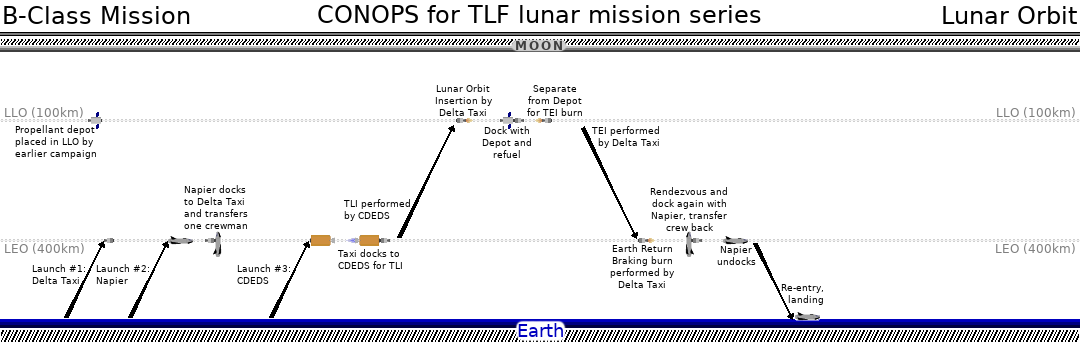

The CONOPS diagram for the B-class lunar-orbit mission.

No firm plans were yet laid out for manned landings, though it was accepted that these were a programme objective; the design criteria for the lander had not yet been settled as it was unclear whether the lander could be a single stage (thus recovered to orbit), or if not whether to use Descent and Ascent stages or Crasher and Lander. There was also the question of whether the lander should have its own integral cabin or whether the cabin of the Delta Taxi should become a separable module. Even the choice of propellants was being debated, although those arguing for a cryogenic lander were a clear minority owing to the low TRL of on-orbit cryocooling.

The first lunar flight was an A-class mission, TLF-1 in February 1964. The Taxi Wayfarer was flown by veteran astronaut Brian Newman, who was carried to orbit in NTF-6 (Napier 2) flown by Arkady Lukashenko on his first spaceflight.

See the full mission report for details and many images.

With the success of TLF-1 it was not felt that a repeat A-class mission would be worthwhile. However, other programmes (such as launching the new Legendre Space Station to replace the ageing Lagrange) required enough of our capacity that it was some time before we were ready to perform a B-class mission.

Meanwhile, design and planning work was ongoing to better specify the lander mission. The lead contender for the lander design was a single-stage vehicle using the Gemini Lander Engine; it is able to get 5km/s ΔV, enough to go from LLO to the surface and back. An advantage of this design is that it is reusable: after refuelling in LLO it can make repeat trips to the surface.

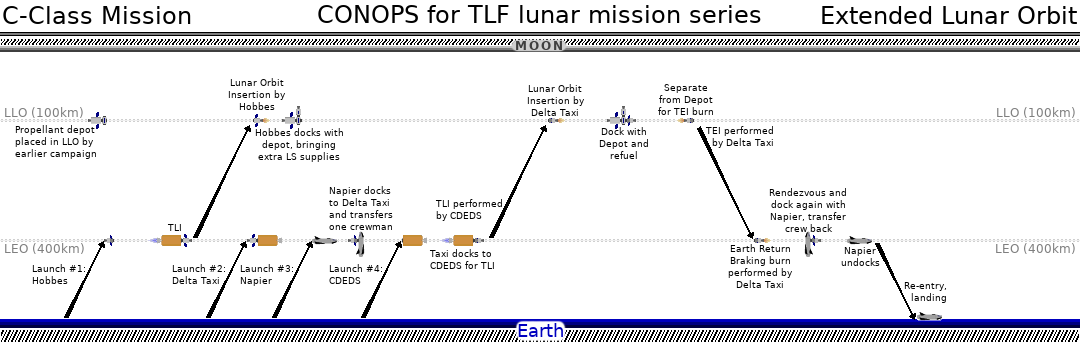

The CONOPS diagram for the C-class extended-duration lunar-orbit mission. Hobbes is a supply craft previously used to deliver consumables to space stations in low Earth orbit.

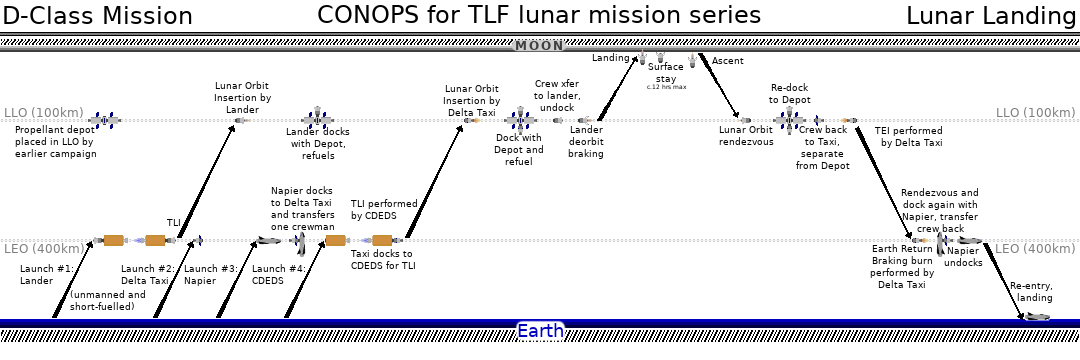

The CONOPS diagram for the D-class lunar landing mission.

The B-class mission took place in October 1964, with TLF-2. Rebecca Reid flew the Taxi Sojourner to orbit the Moon, but experienced very narrow margins of both ΔV and life-support. Fortunately the margins were not quite exhausted, and she and the 'chauffeur' Peter Chapman made it safely home aboard Napier 1.

See the full mission report for details and many images.

Owing to the alarming narrowness of the B-class mission margins, the next mission was planned to be a C-class (i.e. lunar orbit with Hobbes life-support resupply) and use a further improved Delta Taxi variant.

With the upgraded (and reusable) Delta Taxi Mk II "Deliverance", the C-class mission TLF-3 was flown in September 1965. The Napier 1 was flown by Rebecca Reid, ferrying Catherine Graves to Legendre Space Station to meet the Taxi. After a two-day stay in low lunar orbit, Catherine returned safely to the Station and Rebecca flew an impeccable re-entry to land at the Cape.

See the full mission report for details and many images.

Meanwhile, the prototype lunar lander was almost ready for its shakedown flight in Earth orbit.

The test flight of the lander, callsign Prototype, launched atop Locke 2C1 on 3rd October 1965. Unfortunately the RL10 engine of the CentaurC+ upper stage failed to ignite; possibly the 9g acceleration of the Locke damaged some part. Although we were able to make some rudimentary tests of a few lander components during the suborbital arc, the mission was undoubtedly a failure and at T+13m the Prototype hit the Atlantic Ocean at 61m/s.

The replacement lander, callsign Experiment, launched on Locke 2C1a on 10th November 1965, and successfully docked with Legendre Space Station. This was followed on December 8th by Leibnitz DH14, carrying the Napier 2 for NTF-12; rookie pilot Virginia Perez flew the spaceplane, ferrying Rebecca Reid to the Station to board Experiment for LPF-1a.

After separating from the Station, Experiment made an 861m/s burn to ascend to 4,598×402km. This orbit was chosen so that the lander would make two orbits in the time Legendre made three, at the end of which they rendezvoused and docked again. Rebecca spent 4½ hours in the elliptical orbit, and a total of 7½ hours in free flight before returning to Legendre.

To avoid a night landing, we decided to bring NTF-12 down in Australia. About 22 hours after launch, Napier 2 returned safely to Earth.

See an unsorted folder of images from this mission.

The first manned mission to the lunar surface, TLF-4 / LSE-1, took place in April 1966, with the landing itself occurring on the 26th of that month. Brian Newman was the lucky astronaut piloting "Deliverance" to lunar orbit and landing Frontier in Mare Serenitatis, while Napier pilot Arkady Lukashenko stayed at Legendre Space Station. Brian's stay time on the lunar surface was 3 hours and 47 minutes (the lander having consumables and battery life for a maximum of 24 hours, we decided to keep plenty of margin in hand).

See the full mission report for details and many images.

Rather than just repeating the quick flags-and-footprints run, the funding agency wanted it followed up with a longer surface stay duration. This created a requirement for a new, more capable lander; fortunately, the ΔV margins observed with LSE-1's lander were more than enough to accommodate the additional life-support systems required. The new lander, Adventure, went to LLO at the end of August, to wait at Lebesgue for its first crew to arrive.

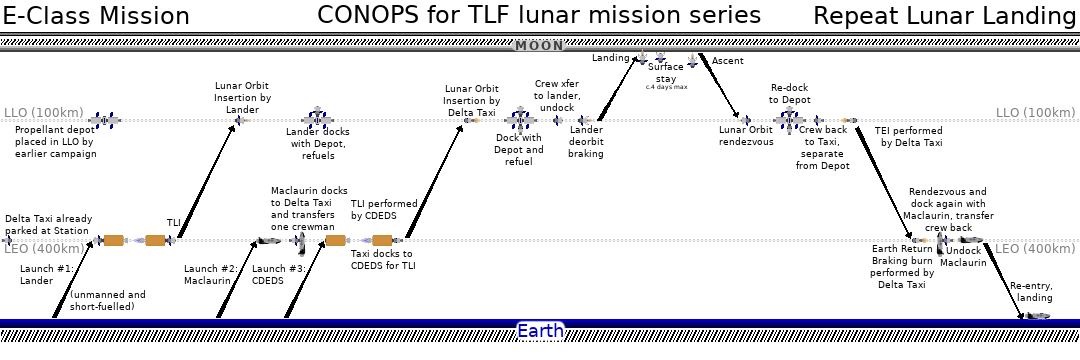

The CONOPS diagram for the E-class lunar landing (extended stay time) mission.

The first priority, however, was to develop the new "Maclaurin" spaceplane. Powered by an RL10A-3-3A engine giving 2,460m/s of ΔV, and massing 6⅔ tons dry, the six-seater spaceplane first launched on 22nd September 1966 atop Galvani CH1. Galvani is an intermediate LV between the Leibnitz and Euler families; using a J-2S sustainer in place of the Tartaglia's LR105, and short-fuelling the Locke boosters to fit on the same 150t pad as the Leibnitz, Galvani had previously only flown twice, once to launch a heavy geostationary comsat and once to send the lander Fahrenheit 3 to Mars. The test flight of the new spaceplane, MPF-1, was flown by Peter Chapman.

See an unsorted folder of images from MPF-1.

With the new spaceplane in service, and the upgraded lander all ready, we went ahead with the first E-class (extended surface stay) mission, launching MTF-1 on December 16th to begin the TLF-5 campaign. The lander, piloted by Rebecca Reid, reached Mare Orientale on December 21st and stayed for 66 hours; the Taxi arrived back at Legendre Space Station on the 29th and all crew were returned to Earth on the last day of the year.

See the full mission report for details and many images.

In 1967 we hope to run at least one more E-class mission, as well as adding to our facilities in orbit of Earth and the Moon — developing the latter into a fully-fledged space station. A two- or three-man Taxi is also a possible line of investigation, though would doubtless call for a larger EDS. Perhaps the Agena family of engines can be developed to provide the ERPS for such a vehicle.